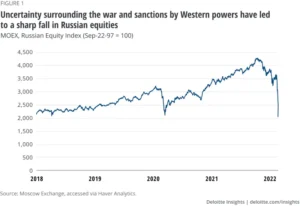

Are sanctions actually hurting Russia’s economy, Just a while back, the U.S. also, several united nations demanded uncommon sanctions against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine.

For quite a long time afterwards, the Russian ruble’s worth failed, unfamiliar worldwide companies pulled out of the nation, and monetary prospects started looking inauspicious.

Yet, Russia responded aggressively. It shored up the ruble’s worth and increased oil exports to China and India.

The ruble is presently the world’s strongest performing cash. Thanks to years of preparations, Russia has become undeniably more self-sufficient, and has massive unfamiliar trade reserves. It has also resumed several companies that were previously under unfamiliar administration, similar to Mcdonald’s.

So, are sanctions working?

“It depends on the standards,” Russian political researcher Ilya Matveev said. “On the off chance that the objective is a fast and complete collapse of the Russian economy, then no, sanctions are not working because the Russian economy is still working. However, in the event that the objective is to debilitate Russia financially more than time, sanctions are 100 percent working.”

We analyze how Russia prepared for this second, and how might affect its conflict on Ukraine.

After it attacked Ukraine in February Business Fellows Class of 2022, dozens of countries responded by quickly transforming Russia into the world’s most sanctioned country.

Some of the most significant sanctions included eliminating several significant Russian banks from the SWIFT installment clearing organization; freezing Russian assets in outside countries; restricting imports of Russian oil; and removing key exports to Russia like super advanced components and microchips.

While the sanctions caused some quick harm, the Russian government has spent years getting ready for a situation like this. At the point when it confronted sanctions in 2014 in the wake of adding Crimea and sending off a “mixture battle” in eastern Ukraine, Russia started attempting to sanction-evidence its economy.

In 2013, for instance, Russia imported about portion of its food; yet today, it is self-sufficient in basic food supplies and has even turned into a significant exporter of items like grains and wheat, as per Chris Weafer, the CEO of the Moscow-based consultancy Macro Advisory.

Prices were at first high and the nature of numerous products like bread, cheese and breakfast cereals fluctuated.

“We went through two or three years of eating what I could best describe as enhanced tissue paper as they were attempting to take care of business,” Weafer said of numerous Russian foods around then. Presently, he said Russian companies had the option to meet a significant number of the country’s food needs, as well as other basic supplies like detergents.

“This is the sort of thing that would be an issue in a couple of years’ time,” Weafer said. “On the off chance that Russia gets in a situation where it needs to reconstruct and wants to return to public projects, it should get cash. And afterward, that may be troublesome because of the present default.”

The ruble’s worth was also high “for some unacceptable reasons,” as per Michael Alexeev, an economist at Indiana University Bloomington — essentially because Russia’s national bank restricted exchanges of the ruble, and Russian businesses had kept up with high exports as imports plunged, resulting in a record exchange surplus.

“Assuming you acquire in dollars and you spend in rubles, the more fragile the ruble, the better,” Weafer said. “So the national bank is presently in a quandary…the current rate is around 54 [rubles] against the dollar. The Finance Ministry and Economy Ministry say it should be 75 to 80. Yet, the national bank are scratching their heads as to how they can do that without risking a collapse.”